Does the weather phenomenon really control the winter season?

It was late summer. The first ski magazines arrived in the mailbox. And then the forecast came in— for the second year in a row, a La Niña pattern was confirmed. Did this forecast have any real bearing on the upcoming winter? Or is it just early season fodder for the weather and ski media?

I still recall my first introduction to the El Niño / La Niña weather phenomenon. It was actually in a “Saturday Night Live” sketch back in 1997. Chris Farley was playing the role of El Niño for the Weather Channel. He was dressed in something akin to a Lucha libre wrestler’s outfit, bare-chested and full of bluster. Acting as a meteorological force to be reckoned with, he demanded other storms bow to him. As a kid right out of college, I found it to be pretty hysterical.

In the years since then, we’ve all grown accustomed to hearing the weather experts announce the confirmation of El Niño or its counterpart La Niña. These two patterns can affect weather and the jet stream worldwide. So for anyone living in a ski town relying on winter storms and snowfall for work and play, a forecast for one of these two patterns can feel like a tarot card reader spelling out your fate.

The official scientific term for the pattern is the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The weather patterns result from sea-surface water temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. An El Niño occurs when the water in that region is warmer than average. La Niña results when it’s colder. The effects of those temperature differences can steer the jet stream in ways that affect the weather all across North America.

When an El Niño is confirmed, the jet stream tends to flow over the southern part of the U.S. That results in wetter and cooler than average conditions. Conversely, the northern half of the country is often warmer and drier.

In a La Niña pattern, it’s the opposite. The jet stream follows a more northerly track. The Pacific Northwest, Northern Rockies and southern Canada see above-average precipitation and cooler temperatures. The southern half of the U.S. tends to be warm and dry.

But how significant is this weather pattern, and how much responsibility does it deserve for our current conditions? Considering the meager snowfall we’ve had thus far and the hot and dry conditions across the southwest, it sure seems ENSO is doing its thing. Headlines of flooding in coastal British Columbia and canceled World Cup races in Lake Louise due to too much snow also seem to confirm La Niña as the culprit.

So as I rode my town bike around the dry streets of Aspen, pondering an ongoing forecast for warm temperatures and zero precipitation, I couldn’t help but wonder if La Niña will be calling the shots all season long?

To help me understand, I spoke with a friend who knows a lot about the topic. Sam Collentine lives in the valley and is a forecaster for OpenSnow, the popular snow forecasting app for skiers and snowboarders. He graduated from CU with a degree in atmospheric science and can talk about weather and forecasting all day long if you let him.

For historical context, Sam told me that fishermen first observed the warming waters of El Niño in the 1600s. They originally called the phenomenon the El Niño de Navidad, or “Christ Child” because it occurred near Christmas.

He told me that it doesn’t have to be one pattern or the other year-to-year. Some years, the Pacific water temperatures are average, indicating neither. Inserting some meteorological wit, Sam referred to those years — when neither El Niño nor La Niña is confirmed — as “La Nada.”

Colorado, Utah and the Central Rockies tend to straddle the boundary between the jet stream flows of the two patterns. Historically our region isn’t as affected as dramatically as the southern or northern states.

Aspen can have a good winter in either situation.

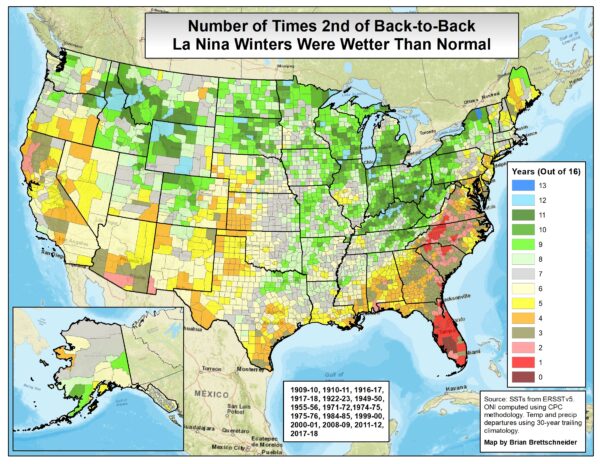

Despite what we’re seeing right now, Sam pointed to some historical data as evidence that we can do well in a La Niña year. Of the past 16 times that we were in the second year of back-to-back La Niña’s — our current situation — Pitkin County registered above-average precipitation in nine of them. In other words, if history is any indication, there’s a greater chance we’ll see above-average precipitation this year than not. We should all find that encouraging.

ENSO isn’t the only game in town either. While it can affect weather worldwide, other patterns can stir things up. The Pacific North American Teleconnection, or PNA, is one of those. It’s used for shorter-term forecasting and can indicate turbulent periods for regions across the U.S.

Put in layman’s terms, it can override an existing ENSO pattern, and it’s currently showing a shift to more storms across the west for the next two-week period. By the time this story goes to print, the first of those storms may have already arrived.

On that note, Sam mentioned that it’s common to hear a lot of chatter about this topic whenever it’s a challenging early season. But eventually, storms materialize, the season gets rolling and ski areas open their terrain. Then everyone goes skiing, and the topic disappears from the conversation.

I think that was Sam’s way of recommending I chill out and realize that it will all be okay.

I followed up with the straightforward question: “So you’re saying it’s going to snow?” To which he replied, “Yeah, I would hold tight and wouldn’t worry about it too much.”

We’re all going to hold you to that, Sam.

In the meantime, if you’re heading up the gondola and the warm, dry weather has you down, pull up the Chris Farley clip on your phone. It will cheer you up while we wait for winter to arrive.

Leave a Reply