Does green mean go?

As we rolled into the New Year, the skies were clearing from a massive storm cycle. It was the snowiest holiday period in years, the kind of weather that locals in a ski town hope for every season but seldom get.

And while some lamented the emergence of the sun and end to the powder, what came next was equally significant — an extended period of unusually stable snow in the backcountry.

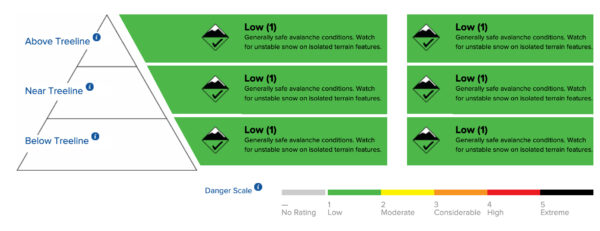

Avalanche risk in the United States is measured on a five-tier scale of increasing risk. The rating ranges from low to extreme, with corresponding colors to visually aid those forecasts. During average years in January, the backcountry avalanche risk in Colorado hovers somewhere in the middle of the range — moving among moderate, considerable or even high on occasion. That’s yellow, orange or red, respectively.

But this year has been different. Soon after the holidays, we found ourselves in a prolonged period of low avalanche risk, a rating assigned the color green.

Weak layers in the snowpack result in instability. They come in various forms — unsupportive ground layers, deep persistent layers, buried surface layers — all of which can contribute to dangerous avalanche conditions. Unfortunately, in some winters, our snowpack suffers from several of these ailments simultaneously.

Thanks to all the holiday snow, we’re in a different situation. I spoke with my friend Greg Shaffran about it recently. He’s a local avalanche forecaster and AIARE (American Institute of Avalanche Research and Education) instructor. He laid it out plainly: “That Christmas storm kind of shielded a lot of those lower weak layers.”

While that snowpack shield is in place, we’re enjoying a higher level of stability, and that is undoubtedly good. It’s certainly reassuring to see the green color in the forecast graphics. When we think of a traffic light turning green, it implies that it’s safe to proceed. But when it comes to backcountry skiing, does green mean go?

A recent forecast from the Crested Butte Avalanche Center (CBAC) followed up the low danger rating with the statement, “We are in a rare mid-winter window of generally safe avalanche conditions. It’s a great time to travel in the mountains.”

This period of higher stability has allowed the backcountry community to get out and ski more aggressive lines. If you can catch a view from the top of the local ski areas or some other vantage point, you’ll see ski tracks everywhere. From Marble to Lincoln Creek, skiers and riders have been in all the local backcountry zones.

Even the mountaineering routes are getting hit. Various steep couloirs and 14ers — lines that are normally reserved for late spring — have seen skiers this past month. Locals have pounced on this period of sun and stability to ski the Maroon Bells, the Pearl Couloir on Cathedral, couloirs off Pyramid Peak and others. Castle Peak has been skied repeatedly.

Some other locations have been outright busy. The lift-accessed lines of Highlands Ridge have been getting skied daily. I can’t recall a time when I’ve seen so many ski tracks in Maroon Bowl.

All the activity, combined with the low avalanche risk, gives the appearance that everything is safe. But that’s not the whole story.

It’s helpful to define what a low avalanche rating means. According to Shaffran, “On the North American danger scale, a low avalanche risk specifies that small avalanches are possible in isolated areas or extreme terrain. Low does not mean no avalanches.”

The high stability translates to generally safer conditions, but there is still a chance of avalanche. The green light isn’t intended to serve as an all-clear. It doesn’t indicate everything is totally safe. And let’s not forget the countless other non-avalanche risks that still exist and have to be managed each time you head out.

Shaffran also likes to remind students in his classes that just because others have skied a line before, that shouldn’t be viewed as a green light either. He cautions skiers not to make decisions based solely on the fact that others are out there skiing big lines. It’s still critical that you go through the standard planning and assessment you would during more regular seasons.

I’ve always strongly agreed with that sentiment. Of course, knowing others have been skiing safely in the same zone may be reassuring. But you and your partners still need to make real-time observations and decisions when you’re out there yourself.

I’ve been able to get out during this period of stability. Even though I found conditions to be generally stable, there were still plenty of concerns.

On one recent tour, we found wind loading to be an issue. We continually encountered 3-6 inches of wind slab that predictably broke under our feet as we skied. It was manageable and somewhat expected. But if you were caught by surprise, you could go for a ride. If it was steep or the slab broke while you were in the trees, that could be problematic.

On a different day, we noted a lot of surface sluffing on north aspects. We had to be mindful of that while skiing, there was a risk that we might get “sluffed out” and knocked off our feet. Like the wind slab, sluffing can also be managed safely. But again, if it happens unexpectedly and you’re above rocks of a cliff, you could get hurt.

In locations where the early season snow had already avalanched, the snow depth was much shallower and less supportive. That wasn’t a significant issue at the time, but the next time it snows, those areas could be particularly sensitive.

These observations occurred on days in the backcountry where the rating was low. They weren’t serious hazards, but they’re good examples of how you could find yourself in trouble even when the lights on the dashboard are flashing green. That’s important to acknowledge.

Low avalanche risk contributes to safer outcomes. But there are still countless other hazards lurking in the backcountry. Planning and good partners will always be paramount. Standard safety protocols still need to be followed.

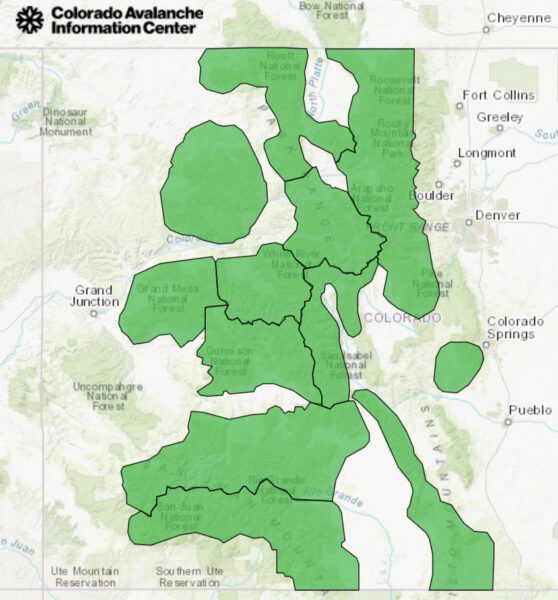

For backcountry skiers, we’ll see how long conditions remain stable. If you’re interested in following the local avalanche trends, consider signing up for the daily forecast emails from the Colorado Avalanche Information Center at avalanche.state.co.us or the CBAC at cbavalanchecenter.org. The services are free, and they’re a valuable source of information to help you stay informed of local conditions.

At the time of this column, the CBAC avalanche warning was still low for all elevations. But if you’ve been at it long enough, you know that whether it’s low, moderate, or considerable, the same rules apply. Avalanches can always occur. Low risk doesn’t mean no risk.

Leave a Reply