The usual trail races are coming up (Lake City, Hardrock) so Christy and I are trying to make the annual rapid transition from skiing to running. It always feels kind of last minute– a recent sprained ankle didn’t help– but while I often complain to myself about the lack of time to get properly prepared, I know deep down I really like it this way.

The usual trail races are coming up (Lake City, Hardrock) so Christy and I are trying to make the annual rapid transition from skiing to running. It always feels kind of last minute– a recent sprained ankle didn’t help– but while I often complain to myself about the lack of time to get properly prepared, I know deep down I really like it this way.

That said, it can be hard to motivate to head out sometimes. Christy left our place the other morning with a headlamp in order to log a long run in the only time available to her, early before work. When you consider how long the days are right now, the fact that she needed a headlamp should be a clue as to how early it actually was. But be it an early start or mid-day battle with the heat, no matter how our enthusiasm measures beforehand, once we’re out the door, everything changes for the better. Sure, the exercise part of the run feels great, but the lesser known and often better reason for running is that by the time we get home we’ve usually sorted out all kinds of things in our heads.

For whatever the physiological reason, when I’m out on the trail my mind has an increased level of focus. At a certain point, distractions and the din of everyday life disappear, and I find myself “zoned out,” focusing on a singular thought as I move along the trail. Eventually I’ll come out of this day-dream like state, only to wander off again in my mind, in a cycle that can go on for hours. Afterwards (and much like a dream) I might not remember all of the details that passed through my head, but in a general sense, everything is clear. Questions are answered, petty problems are solved, and ideas both big and small might be hatched. Christy’s been in tune to this for a while and has actually started carrying a voice recorder with her because she gets a ton of work-related thinking done on her runs, and she doesn’t want to forget anything.

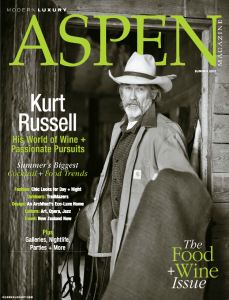

I wanted to share a story we were recently interviewed for in Aspen Magazine about Aspen trail running and where I summed up trail running this way:

“I often reach a point where I am no longer actually thinking about my effort level and, instead, find myself in a different mental space…. Gone are any thoughts or concerns that were top of mind when I started, which makes trail running about so much more than just a good workout.”

The full story is below. And if you see Christy on the trail talking into her hand, don’t interrupt her, she’s in a deep thought.

Counter Culture

Elinor Fish | May 21, 2013

Here’s an inside look at Aspen’s extreme trail running scene.

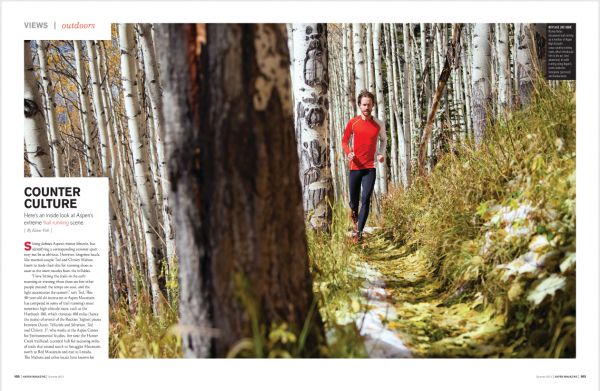

Skiing defines Aspen’s winter lifestyle, but identifying a corresponding summer sport may not be as obvious. However, longtime locals, like married couple Ted and Christy Mahon, know to trade their skis for running shoes as soon as the snow recedes from the hillsides.

“I love hitting the trails in the early morning or evening when there are few other people around; the temps are cool, and the light accentuates the scenery,” says Ted. This 40-year-old ski instructor at Aspen Mountain has competed in some of trail running’s most notorious high-altitude races, such as the Hardrock 100, which traverses 100 miles (hence the name) of several of the Rockies’ highest passes between Ouray, Telluride and Silverton. Ted and Christy, 37, who works at the Aspen Center for Environmental Studies, live near the Hunter Creek trailhead, a central hub for accessing miles of trails that extend south to Smuggler Mountain, north to Red Mountain and east to Lenado. The Mahons and other locals have known for years what the larger trail-running community is just starting to discover—that Aspen is one of the country’s top trail-running destinations.

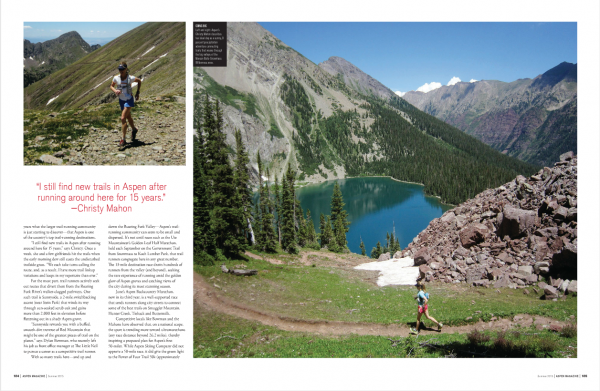

“I still find new trails in Aspen after running around here for 15 years,” says Christy. Once a week, she and a few girlfriends hit the trails when the early morning dew still coats the undisturbed trailside grass. “We each take turns calling the route, and, as a result, I have more trail linkup variations and loops in my repertoire than ever.”

For the most part, trail runners actively seek out routes that divert them from the Roaring Fork River’s walker-clogged pathways. One such trail is Sunnyside, a 2-mile switchbacking ascent (near Stein Park) that winds its way through sun-soaked scrub oak and gains more than 2,000 feet in elevation before flattening out in a shady Aspen grove.

“Sunnyside rewards you with a buffed, smooth-dirt traverse of Red Mountain that might be one of the greatest pieces of trail on the planet,” says Dylan Bowman, who recently left his job as front office manager at The Little Nell to pursue a career as a competitive trail runner.

With so many trails here—and up and down the Roaring Fork Valley—Aspen’s trail-running community can seem to be small and dispersed. It’s not until races such as the Ute Mountaineer’s Golden Leaf Half Marathon, held each September on the Government Trail from Snowmass to Koch Lumber Park, that trail runners congregate here in any great number. The 13-mile destination race draws hundreds of runners from the valley (and beyond), seeking the rare experience of running amid the golden glow of Aspen groves and catching views of the city during its most stunning season.

June’s Aspen Backcountry Marathon, now in its third year, is a well-supported race that sends runners along city streets to connect some of the best trails on Smuggler Mountain, Hunter Creek, Tiehack and Buttermilk.

Competitive locals like Bowman and the Mahons have observed that, on a national scope, the sport is trending more toward ultramarathons (any race distance beyond 26.2 miles), thereby inspiring a proposed plan for Aspen’s first 50-miler. While Aspen Skiing Company did not approve a 50-mile race, it did give the green light to the Power of Four Trail 50k (approximately 31 miles), which will follow a course identical to the mountain-bike race by the same name.

But for most trail runners, logging off-road miles is not about competition as much as it is about a sense of adventure and personal accomplishment. That’s why the Four Pass Loop in Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness area tops many trail runners’ bucket lists, ranking up there with running the Grand Canyon rim to rim.

Backpackers typically tackle the Four Pass Loop in three to four days, pitching a lightweight tent and cooking over a tiny camp stove each night. Trail runners cover it in a day, carrying a whisper-light hydration pack, shell jacket, water filter and a few thousand calories’ worth of energy food.

“Four Pass Loop is one of the country’s most iconic trail runs,” says 32-year-old Rickey Gates, who was born in Aspen and holds the fastest known time for completing the 28-mile loop around the Maroon Bells in an astounding four hours and 36 minutes. “I love the challenge of running four passes above 12,400 feet and the incredible views it offers of Snowmass Mountain, the Maroon Bells and Pyramid Peak.”

Starting at the Maroon Bells parking area in the predawn darkness hours before the tourist hordes arrive by bus, runners travel either clockwise or counterclockwise, alternating power hiking with efficient, short-and-quick run strides to pick their way over the often rocky footing.

When going counterclockwise, the trail snakes over West Maroon Pass, then leads to Frigid Air Pass, which offers a clear view of the back of the Maroon Bells en route to Trailrider Pass. From there, the trail descends in a loose, rocky switchback series to icy-cold, shimmering Snowmass Lake at the base of Snowmass Mountain’s vertical iron-gray walls. A popular camping locale for hikers, it provides trail runners with a shady rest stop for rehydrating and scarfing an energy bar to fuel the day’s last and most arduous climb up and over Buckskin Pass.

When asked why trail runners gravitate to long, relatively remote routes like the Four Pass Loop or the relatively mild Conundrum Creek—which offers a very runnable and scenic 9-mile jaunt to a natural hot springs—the answer is about tapping into the sport’s “Zen-inducing” effect that isn’t achieved in road running.

Whereas many road-runners plug into their favorite tunes to tick off the miles, trail runners report that the ever-changing natural terrain under their feet and the stirring scenery before their eyes cause time and distance to pass unnoticed. “I often reach a point where I am no longer actually thinking about my effort level and, instead, find myself in a different mental space,” says Ted. “Gone are any thoughts or concerns that were top of mind when I started, which makes trail running about so much more than just a good workout.”

4 Comments

Leave your reply.