Life can be hard on our bodies. Adventuring in the mountains doesn’t make it any easier. After years of tackling all sorts of challenges on foot, ski, and bike, it shouldn’t have come as a surprise to learn that I had worn out one of my joints. I had my left hip replaced back in December.

When I tally the miles covered and the vertical gained, and add a few crashes and minor injuries through the years, I’m not surprised that some part of my physical self eventually called it quits. After all the races and summits and time on the trail, I actually consider myself lucky to have been able to cover as much ground as I did with my original parts.

I can spend days discussing the details of how I reached this point– the warning signs that I downplayed, the exhaustive steps I took to manage what I always thought was just a tight hip flexor, etc.

So I’ll try to keep it short. The fact is, cartilage loss doesn’t happen overnight. The process of joint deterioration occurs over years, if not decades. In hindsight I recall certain moments, some more than 10 years ago, when I first noticed issues in my left hip. I normalized those issues over time, and like a lot of athletes I just excused the ongoing symptoms as the result of overuse.

Spread out over years, it’s hard for anyone dealing with cartilage loss to really notice the incremental deterioration. It happens so slowly that it’s easy to miss the fact that your condition is actually getting worse. That is until it gets really bad.

As my own symptoms of tightness and soreness worsened, I often laid the blame on the fact I was getting older, and that with my increasing years I shouldn’t be surprised to be a little more stiff and tight. I told myself I just needed more time on the mat, stretching and rolling, and additional visits to the masseuse and acupuncturist.

Denialism is a pretty powerful human behavior. Sometimes a friend would tell me it looked like was limping, or a PT reported asymmetrical weakness in the area, or a noticeable decrease in my range of motion. My answer: shrug it off and do some more targeted strength work, more stretching, maybe take a rest day here and there.

While those steps certainly helped, they only delayed the inevitable. After continuing to run the ultras and chase big outdoor goals, the joint eventually decided that enough was enough. One day in August 2019, I went for a run along a local bike path, and after a few minutes, I experienced a sharp, shooting pain, like an electric shock. I turned around and walked home, confused.

Every run afterwards ended the same way. It didn’t matter if I took extra rest days, stretched a lot beforehand, or saw any of my preferred body work friends. I could only run for a few minutes before the sharp shocking pain forced me to stop. I was still able to walk, hike uphill, and sometimes shuffle downhill, but from that day on I never really went for a proper run again.

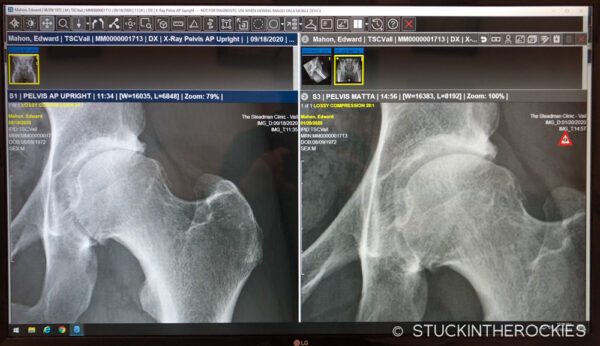

I set up appointments with different hip specialists around Colorado in the weeks and months that followed, and the diagnosis was clear. X-rays showed moderate to advanced osteoarthritis, and the amount of cartilage loss was beyond what would allow for any repair procedures. Three different orthopedic surgeons all told me the same exact thing— a total hip replacement was inevitable.

They recommended I stop doing anything that hurt. Two of them bluntly advised that I “just stop running” and do other activities. As someone who has made running a primary focus for the past 15 years, the matter-of-fact presentation of my limited options was tough to process.

Because the replacement joints don’t last forever, hip specialists are reluctant to offer the replacement option until you reach a certain age. I was 47 years old, which put me on the younger side of what conventional medical wisdom considers a replacement candidate. Two of the ortho’s I saw insisted I get another 5-10 years out of the hip. I wasn’t sure if that was possible. The third doctor, aware of my level of activity, and that I work on my feet in summer and winter, seemed to understand the potential urgency to get me back to normal should things get any worse. He offered to do the procedure if I reached a point where I felt it necessary.

Long story short, I made it about another 15 months. I had two cortisone shots in the interim, the first one offered some relief for about 6 months, the second one didn’t help at all. Soon after that, by late fall 2020, I was having a hard time walking even one mile. The winter season was approaching, and it seemed impossible to expect to be able to work on skis, day-in day-out, through the winter. Rather than wait any longer, I set up the procedure for the next available date.

In early December I went in for the surgery with Dr. Joel Matta and Dr. Joe Ruzbarsky at the Steadman Clinic in Edwards, CO. The entire visit took six hours, and I walked out on my own two feet (with the support of crutches) and was home in bed that night. It was an amazingly easy procedure.

It’s now been ten weeks since that day, and I couldn’t be happier. It was a 3-4 weeks of feeling like a patient, and after that I’ve been improving rapidly, and easing into increasingly normal activities. At this point I don’t think much about that fact that I have a prosthetic joint. Apart from the scar and the area of the surgery, there’s very little to remind me that I had anything done at all. It’s really pretty amazing.

The general consensus for this procedure is that I should be back at 100% soon. Of course it’s hard to know what 100% really means. The average 48 year old’s definition of 100% is probably much different than mine. So I don’t know. Skiing? Sure. Biking? Of course. Running? Probably, but at what level, I don’t know. I’ll just have to wait and see what the future might bring.

13 Comments

Leave your reply.